|

I’ve been doing research to follow up on my recent WW II Quarterly article on Merrill’s Marauders in Burma. I’m now interested in the activities of the OSS in Burma, specifically the OSS 101 detachment and also the Kachin Rangers who supported both Merrill’s Marauders and the OSS 101 detachment. During my visit to Myitkyina in north Burma last year I learned there are members of what they term the Kachin 101 group still alive and very proud of their service with the OSS during the war.

One stop I decided to make at home here in the US, was to Arlington National Cemetery where the founder of the OSS, Maj. General Bill Donovan is buried. Here are pictures of Maj. General Donovan’s headstone and Arlington National Cemetery which holds over 400,000 graves of American and allied warriors. I note that Maj. General Orde Wingate, the founder of the British Chindits unit, is also interred in the cemetery in a joint grave site with the crew of the C47 aircraft he was with when it crashed into a Burmese mountain side in March 1944. These are people and stories that should not be forgotten.

0 Comments

When writing military history, especially concerning a landmark battle, it’s best to walk the ground whenever possible. For this reason, as research for a piece I’m writing on Merrill’s Marauders in WW II, I felt I had to go to Myitkyina the capital of the Kachin State in north Burma to physically embrace the setting of the Marauders greatest and final achievement, the march on Myitkyina and the seizure of the strategically important airstrip adjacent to the town.

When at the scene however I was overwhelmed with all the historical dimensions I discovered in that small corner of Burma. The ties to the past are numerous as well as the present day issues growing from the past. The Kachin people, whose Kachin Rangers were outstanding fighting allies of the U.S. army in Burma, have been engaged in a war for independence essentially since Burma declared independence in 1948. As a result of Burmese army actions there are over 98,000 displaced persons, primarily Kachin and Shan tribes people, living in 170 refugee camps in the two states today. There is a group in Myitkyina, called the 101 group, which represents the Kachin people and the families of those who fought with the OSS 101st detachment in Burma. Merrill’s Marauders are well remembered by this group. Also I came across a group representing the soldiers of the Chinese Divisions who fought the Japanese, under the command of General Sun, Li-Jen, some of whom remained behind in Burma when the war ended. Myitkyina, a town of 300,000 population, has a community of 20,000 Chinese primarily derived from those soldiers. I met with family members of these Chinese soldiers and learned of the Chinese communities’ recent effort to recover the bodies of 347 Chinese soldiers killed during the fighting in May to August 1944 from a mass grave. This war time burial site was located in a residential area of town. The residents in the area didn't know of the grave but some of the old soldiers still alive from that period knew the general area and when interviewed were able to direct members of the Chinese community to find it. That excavation was completed over a year ago. Wikipedia says 972 Chinese were killed during the fighting and 272 Americans. I spoke with a lady named, Yang, Ling Ling, whose father fought in the battle for Myitkyina and died in 2011 at the age of 91. She helped supervise the operation in the memory of her father. She said of the bones they recovered, "these were my father's friends." The pics here show the site where the bodies were recovered which has stones and landfill on it plus some trees recently planted. Note the nearby bamboo house. The occupants were surprised to learn of the grave under their front yard. There is a school and soccer pitch across the dirt street and it is believed there may be another mass grave site under the soccer pitch. We went to the cemetery where the bones are being kept in plastic boxes, one body to a box, in a cinder block hut as the plan was to ship them home to China. General Sun promised his soldiers that if they died in the fighting they “would go home” after the war. Yang, Ling Ling in the picture, was in tears as she prayed before the bones. She said that when she asked her father why he didn't go back to China after the war with the Japanese, he told her that in China it would be "brother fighting brother," and he didn't want to be part of that. A very sad and moving story and one that is still not finished. There are more mass burial sites within the town. I was told that two weeks ago a road repair crew in town found bones under the road they were working on. There is a temple built by a Japanese group seeking to honor the dead and a plaque to the 3,400 Japanese who died in the battle. Note: Wikipedia says 2,400 Japanese died in the battle but the plaque put up by the Japanese government says “3,400 flowers fell” at the site. I feel I should honor the Japanese numbers on this matter. I came away with a better understanding of the chaos that was the battle for Myitkyina, but also feeling that a return visit is in order. There is much to be learned there. Upon retirement from the business world in 1998, I approached the Human Development Foundation, also known as the Mercy Centre, in Bangkok to see if they would accept me as a volunteer. They invited me in and I thought it would be for a year or two. Now fourteen years have passed and I have been privileged to work as part of a miraculous organization in Thailand. Recently, I had occasion to visit a project Mercy has been working on for four years in the South of Thailand that provides education and health assistance to the Moken people, often known as “Sea Gypsies,” living on the island of Koh Lao. This island is a thirty minute boat ride from the Thai fishing town of Ranong, located on the Andaman Sea along the Thai border with Burma.

The Moken are an indigenous nomadic tribal people, numbering between 2,000 and 4,000, who have lived and fished on the islands of the Andaman seas for over a thousand years. They have a unique language with no written form and very often don’t speak either Thai or Burmese. They are animists and worship the gods of the sea. The village I was going to visit has fifty families and a population of approximately 370. This makes it one of the largest of the Moken groups scattered along the Andaman coast and islands. As the boat approaches Koh Lao, one of the first things you see emerging from the green jungle background of the island is the collection of wooden homes built on stilts over the water’s edge. Though I am not trained as a sociologist or anthropologist, the thing that jumped out to me immediately was that these are a very close-knit people. What led me to that assumption was that the homes were not spread out but rather clustered together in one contiguous mass, each house almost touching the next so that it seemed you could walk from the porch of one house to the next and make your way through the village in that manner. Possibly it’s done so that a person doesn’t have to get down into the water at high tide to make their way around the village but, whether it’s cause or effect, it came to me, as I met with them and learned a bit about the social life of the Moken, that they are indeed a close knit group. Another thing that quickly becomes apparent is that these people are not living the glorified pastoral life that is sometimes conjured up in National Geographic photo articles, but rather a savage daily fight for survival. When our Mercy staff first approached this village four years ago they found children were dying at the rate of three each month in the first year Mercy worked there. All of the community had intestinal worms which took several treatments over a period of months to eliminate. Now the community is, for the most part, healthy and in the past year only five child deaths have occurred. Mercy’s main program with poor children is education, but you have to protect the children and their health first. Today Mercy has established a preschool on the island, which teaches 35 children the Thai language, provides medical counseling to the community and, most importantly, provides a nutritious lunch each day. Last year Mercy established a home in the city of Ranong to house 20 of the older Moken children so they could attend primary and junior high school at government schools in the city. While the traditional way of life is passing, there is a basis for hope in the future of the Moken children. The life of a Bangkok bar girl has come to an end.

Sunday night Dos died. She hadn’t been feeling well for some time, months, years, who was to know as she didn’t tell anyone until near the very end. She had cancer, internally but we don’t know exactly what organ was the origination point, the stomach, the liver (aaahh the liver, when it comes to the real drinkers, as Dos was, we must always suspect the liver), the kidneys, the lungs as she was a smoker, nodes on all or one of them, we don’t know for sure. It doesn’t matter because Dos didn’t opt for any of the treatments our pain delivering medical advisors rush to prescribe. Dos decided to keep the bad news to herself and continue to live her life as always. She wanted to drink and laugh with her friends until the end. She succeeded in that. Of course when one says living as always about Dos, one is talking about an enormously unhealthy life style in any event. At the time I met Dos, about ten years ago, she was in her mid thirties and definitely not a healthy picture. She was medium height for a Thai girl, possible 5 ft. 4 or 5 inches tall, and quite thin. She had at some point on her path adopted the punk/biker girl look complete with boots with spike heels, chains, always in black, jeans and t-shirts, a tattoo here or there, nothing too flagrant. It was to be sure a bit of a silly picture. It’s hard to project a tough biker girl image when you’re so thin a strong breeze might blow you away. Dos was, for all her adult life and possibly much of her adolescence, a creature of the night. Amphetamine user? Probably, she had been a working girl as they say for some years, but when I met her doing research for my book, “Bangkok Pool Blues,” she was part-owner of a pool hall which also had bar girls for rent and part of Dos’ job was to supervise the girls. Some sponsor, a past customer one guesses, had paid for her interest in the pool hall and was her patron still at times. None of the above really says anything about Dos, just about her situation. I liked Dos. It may seem a bit of a stretch to some given the description above but she was a likable person. An Englishman, a manager at a pool bar she worked at previously as an assistant manager, described her as “sweet” and much too softhearted a manager herself. She always had a smile and wanted to laugh and enjoy life with all. She supervised the working girls but never with a heavy hand that I saw or heard about. It was all just part of life. She did like to drink and many is the time I saw her at the beginning of the evening and she would say she was moving slowly, that the last night had been a bit too much. Certainly when I finished my pool games and went on home she was well lubricated. She would sit outside the door to the pool hall with one or two of the girls, drinking her drink, smoking her cigarettes, greeting incoming customers, saying goodnight to outgoing customers and joking about the absurdity of life. Poor Dos, life was a bit too much for her. It seemed as if she never got a grip on it. Of course she had the absurd part right. She didn’t die well as one might guess. She felt terrible, racked with pain, and went home early, ten or eleven pm, from the pool bar. At home she got worse, had trouble breathing and started to bleed. She called the bar and asked some of the girls to come and take her to the hospital. The girls went and found her semi-conscious and bleeding. An ambulance came to take her to the hospital. She stopped breathing along the way. At the hospital a doctor tried to resuscitate her but it proved impossible. She had died. She was 45-years-old and left a 20-year-old son. Now, a few months later, there is a very Thai footnote to this note concerning Dos. The Thai are very strong believers in the next life and in ghosts. They believe that the ghosts or spirits of the departed often come back to familiar places. In this case it was Dos’ place of work, Jim’s Pool bar. On a recent night the shades were pulled at closing and the all night gambling and card games continued with women seated at the low stakes table and the men at another table playing for much higher stakes. In this case the winner went home the next morning $3,000 up. During the night there was a power outage. This is not unusal in Bangkok, a city whose distribution grid leaves much to be desired. After a few seconds the lights came back on and the games continued. However within a few minutes there came another power failure and everyone immediately understood and yelled out virtually in unison, “Pi Dos ma” meaning Dos’ ghost had come back to visit and was signaling to get their attention. The reaction was laughter and happiness, in reality a sort of tribute to Dos. Of course the important thing, when the lights came back on a few seconds later, was to give Dos’ spirit what it wanted and that was Dos’ signature drink, a Black soda. One of the women went behind the bar and opened a bottle of Black Label scotch, as Dos did each evening, and mixed a strong shot of Black Label with soda water and then placed it, along with a small plate of bar snacks, on the table just outside the front door where Dos sat many a night talking with the girls and greeting customers. Then, with Dos’ spirit content, everyone went back to the gambling. The lights stayed on. There exists, in the crowded squalor of slum huts, open sewage drains under expressway overheads, alongside dirty train tracks, in the poorest areas of this sprawling city of eleven million people, a tribe of warriors whose training for combat starts early in life and never ends. It’s a family-oriented clan that passes the warrior tradition down from generation to generation. In all cases these families have no wealth other then this golden tradition. The members of this group have homes, albeit for the most part these are squatter’s slum shacks thrown up on land alongside the railroad tracks. Though their family lives are important - they work at a variety of basic labor and security jobs and the children go to school every day - it is the training ground that is very much the center of their existence and identity. The training ground is a bit of open-air space alongside the railroad tracks and underneath the expressway. It’s a small lot, no more then 20 meters wide and 30 meters long. It’s surrounded by a chain link fence and has some rough concrete toilets built in a corner at one end. At the other end, taking up almost the full width, is the boxing ring, standard size, three feet above ground with a fence of ropes around the sides. Yes, this is the war that these warriors practice for, the ancient Thai combat art of Muay Thai.

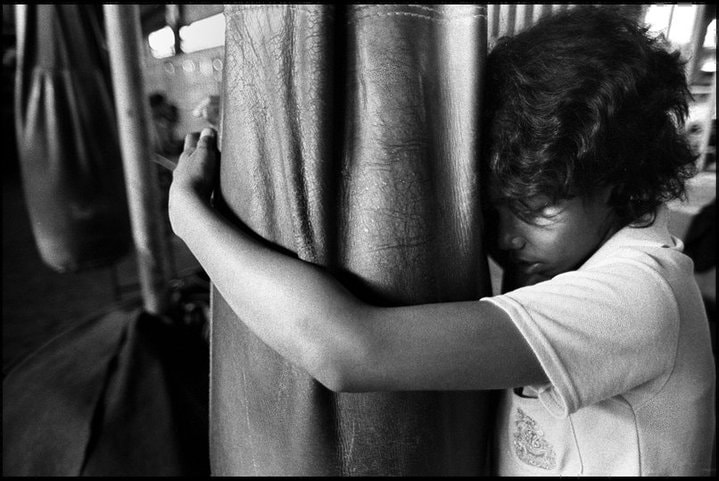

There are 15 children working out today on the 11 large dilapidated kick bags hanging from four iron frames set up around the inside of the gym ground. The ground itself has a rubber covering over the concrete. What they have done, to emulate the composite floor covering of modern gyms, is cut up old truck tires, available from a cross-country truck lot nearby, flatten them out as much as possible and make that the floor for the gym to protect the children, to some extent, when they take falls. The tires are not flattened very well and it is easy to trip on edges and bumps sticking up when just walking around the gym. I have been introduced to this camp, named Penang 96, by the Korean photographer, Yoon‐Ki Kim. Mr Kim has been following and photographing the lives of this warrior clan for ten years and is planning a book chronicling the life of three generations of one of the families. Mr. Kim’s classic black and white photos are an important part of my nonfiction book, “Bangkok Pool Blues,” about the night people inhabiting the emerging pool culture that has grown up in Bangkok over the past ten years. The camp is open every day, except Sunday, from 4pm to 7pm. The children come after school and train until the camp closes. There are about six older males, most in their fifties, in attendance, former fighters, all now carrying excessive weight and no longer in the boxing form they once were. One older guy who looks to be in his sixties, but wearing Muay Thai trunks and gear, is sparring and playing around with the kids. He has a punched-out look and manner, both gruff and kindly, that reminds me of the trainer for Rocky Balboa in the famed Rocky motion picture series. It’s after 5pm when we arrive and the kids are sweating heavily, having worked for over an hour already, in the dense Bangkok heat and the dead, almost noxious air underneath the express way. However what strikes you almost immediately, after getting through the initial introductions to Krue (teacher) Preaw and the older males in attendance, is both the intensity of the kids in training and the happiness they show at being here, in the holiest of holies, Krue Preaw’s Muay Thai training camp at Penang 96. In discussion with Krue Preaw the family angle becomes evident. He is in his late fifties, over thirty years ago he was a competition fighter taking on the best in Thailand at the famed Lumpinee Muay Thai stadium, the pinnacle of Muay Thai competition in Thailand. After that he trained his son Be and others, mostly relatives, some starting to learn as young as the age of ten. Now Be is in his thirties, working as a security guard and Krue Preaw is training, along with many others, his granddaughter Ink, who is 14 and has won a national championship in a children’s Muay Thai competition, and his grandson Chuan who is 13. There are certainly more offspring and more championships in the offing. All in all, it adds up for me to a very impressive story, combining poverty and the poorest of children, who are possessed of an incredible can-do attitude which erupts periodically in smiles and laughter, while at the same time they are working with incredible diligence at learning one of the hardest of martial arts. These kids may be poor but they are rich in family and in the self-confidence their training brings. It’s enough to make you feel sorry for the richer kids who may never be allowed to experience the inner strength they are capable of. The photos below are of Ink preparing for a match and then resting after training, clutching the boxing bag. |

AuthorAuthor of: Mercy's Heroes, Shrapnel Wounds, Bangkok Pool Blues, and the Matt Chance thrillers Viper's Tail, Murder in the Slaughterhouse and Bangkok Gamble. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed